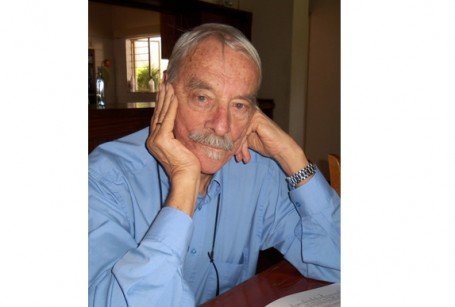

Interview with Stefans Grové at the time of his 90th birthday

04.06.2013 The recently deceased composer Stefans Grové was interviewed by pianist Ben Schoeman on the occassion of his 90th birthday in 2012. In remembrance to this giant of the South African music scene, we are republishing this interview.

Verlag Neue Musik in Berlin published the following biography of the composer:

Stefans Grové was born in 1922 at Bethlehem in the Orange Free State (South Africa). Displaying an early aptitude for music, he started taking piano lessons from his mother at the age of six. By the age of twenty Grové had obtained both his Performer’s and Teacher’s Licentiates in Piano, as well as his Performer’s Licentiate in Organ. In 1948 he graduated at the South African College of Music at the University of Cape Town, and became a lecturer at his alma mater. Grové, a multi-talented musician whose other instruments are the viola and the flute, started his career as a composer at the age of nine. By early adulthood he had begun to win prizes for his original works, even though he had never had any formal training in composition, apart from his own careful analysis of a wide variety of scores. In the early fifties he won a prestigious scholarship, which enabled him to concentrate on composition under the celebrated Walter Piston at Harvard University (USA) and take lessons with Aaron Copland at the Tanglewood Summer School. In 1957 he was appointed to a Lectureship at the renowned Peabody Conservatoire in Baltimore (USA), where he remained for fourteen years. Shortly after his return to South Africa in 1972 he joined the staff of the University of Pretoria as a Professor in Composition. He is still Composer-in-Residence at this institution. Some of the important works composed during Grové‘s early years include his Three Inventions for Piano, heard at the 1953 Festival of the ISCM in Salzburg and his First Symphony, performed by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra in 1966. In 1984 his artistic ideas underwent a thorough innovation when Grové started reflecting his South African musical roots. One of the fruits of Grové‘s “vita nuova” was the Sonata on African Motifs for Violin and Piano. Subsequently more than forty cross-cultural works came into being, tending to incorporate generic features of African music, such as poly-rhythmic metrical structure and modal harmony.

Ben Schoeman: Prof. Grové, you are celebrating your 90th birthday on 23 July and are looking back on a long and colourful career as a composer. I would like to go back to the beginning and would like to ask you why you decided to become a composer. Did you ever consider a career as a performing artist, or were you mainly interested in composition?

Stefans Grové: It was not really a choice, but more of a vocation. I come from a very musical family. My mother was a piano teacher and two of my Roode uncles were professional musicians, and also my sister. It was therefore a necessity for me to become a musician. I started with piano, then the organ and many years later also studied the flute and viola. However, the piano was my first instrument and I was deeply impressed with my mother’s incredible ability to sight-read. Together we often sight-read the symphonies of Haydn. These circumstances led to my interest in improvisation. My uncle, David Roode, was very strict and always said that I should practise the piano and prepare for my lessons before I could improvise. It was through improvisation that I became interested in composition, as I experimented on the piano and then wrote down these musical ideas. Throughout my youth and even during my university studies in Cape Town, I remained an autodidactic composer. My first major teacher was Prof. William Henry Bell (at the South African College of Music). He was very British in his outlook, while I was more interested in the French Impressionists. I knew early on that I wanted to be a composer, as I did not enjoy practising. I was not a bad pianist, but I did not want become a performer.

BS: Upon evaluating your extensive oeuvre, it is interesting to see that you have composed more than thirty piano works. As a pianist I find these compositions particularly fascinating. I met you for the first time in 2004, when I took part in the 10th UNISA International Piano Competition. Your Dance Song for the Nyau Dance was the commissioned work in the first round. I know that many composers find it difficult to write for the piano. How do you experience this?

SG: Of all the instruments that I learnt to play I am most intimately acquainted with the piano and it remains my most beloved instrument. The older I get, the easier it becomes to compose for the piano. My most recent compositions, My Jaargetye/My Seasons (2012)* and the Piano Quintet (2012), contain pianistic elements that I have never used before. These works are informed by my orchestral writing and I use techniques such as the simultaneous use of legato and staccato. I have not seen this in any other piano music – it seems to be my own compositional property.

BS: I would like to refer to a discussion we had in February this year, when we talked about the interpretation of Mozart’s piano music. It is often necessary to use different articulation in the left and right hands respectively in order to bring clarity to the polyphonic lines in this music. Would you say that you have been inspired by this principle? I know that you have a great admiration for the music of JS Bach. Does your emphasis on articulation correspond to your appreciation of early music?

SG: I use the combination of staccato and legato in a slightly different way. The right and left hand usually plays an octave apart and in unison. With this new technique I am creating a distinct sound colour, but it is also an expressive tool in my music. I have often used this in orchestral works, where one group of instruments plays staccato and another legato. This results into a transparent texture and also accentuates certain melodic lines. I find that meticulous articulation on the piano is very important to me, particularly because of the fact that I played the flute and the viola. Many composers only make use of phrase bows, whereas I almost exclusively use articulation bows in my scores.

BS: Apart from articulation, do you have specific views on other aspects of piano playing?

SG: I am an enemy of the excessive use of the damper pedal. Many of my piano works have to be performed without pedal. I use it only in slower, more expressive passages or movements. One sound colour that I am particularly fond of, is to hold a series of chords with the left hand and then to gradually release the pedal in order to create a variety of overtones until the sound dies away.

BS: Do you also make use of the third pedal (sostenuto pedal)?

SG: Yes, very much so. I find the third pedal very helpful when it comes to creating transparency in my piano music. There are many examples of this in the new piano work My Jaargetye (2012). In the third movement (First Spring rain and the awakening of delicate colours) a plethora of colours and overtones is created by holding the opening silent chord with the third pedal.

BS: You mentioned that this third movement of My Seasons is writen in two parts, a fast introduction and a more introspective section. The introduction symbolises the first Spring rain and the slower part that follows symbolises the many colours that appear after the rain. Would you say that visual images often infuence the structure or timbres in your music?

SG: I am a composer of programme music and my works are mostly based on things that I have seen, heard and read. These images stimulate my imagination and I convert them into musical ideas. Dreams are also becoming very important stimuli. I often hear musical material in my dreams and this is very helpful when I start to compose the next day. When the organist Gerrit Jordaan was preparing to perform my Afrika Hymnus No. 1, we met at the Rieger Organ in the ZK Matthews Auditorium in order to discuss the work. The night before the scheduled meeting I dreamt that Gerrit was playing very kaleidoscopic music on the organ. When I asked him what he was playing, he said that it was my Afrika Hymnus No. 2. This might only have been a dream, but this transparent music stayed in my mind and was a great inspiration when I started composing the second Afrika Hymnus.

BS: These dreams almost sound like visions and it reminds me of your description of the so-called ‘Damascus’-moment in your career. In 1984 you heard an African melody being sung by a pickaxe worker in Pretoria and started to integrate this melodic material into the Violin Sonata that you were working on at the time…

SG: Yes, I regard my conversion to Afrocentrism as a ‘Damascus’-moment. Just as St. Paul started a new religious way of life after his epiphany on the road to Damascus, have I started a new creative phase after hearing the African melody that I incorporated into my Violin Sonata. I can refer to the words of Jean Cocteau: “The more a poet sings from his family tree, the more genuine his song will be”. I have composed predominantly Western music before 1984, but I finally decided that my music should reflect the continent on which I live. When I was still a student, a concert devoted to my compositions took place in Amsterdam. One critic praised my work, but he also added that he found it surprising that there was no sign of Africa in my music. This disturbed me for many years and I constantly pondered the possibilities of fusing my Western craft with my South African roots. I can finally describe my style as a synthesis between African stimuli and Western structural principles.

BS: There is a distinct spiritual element in your music-making and for many years you were the organist of the Lutheran Paulusgemeinde in Arcadia, Pretoria. You also add the words “Jesu Juva” (may Jesus help me) at the end of your scores. Do you experience religious inspiration when you compose?

SG: SG: Only in my church music. In my secular music I am inspired by other aspects, including traditional African music that longer exists. The ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey’s recordings of traditional music were particularly important to me. The current African generation have broken away from traditional music – they are not familiar with it anymore. I am stylistically intertwined in history and my aim is to highlight this traditional music. I am a historian who is giving a speech on how things used to be. UNISA is in possession of the complete collection of Tracey’s recordings of indigenous South African music. His descriptions of South African music inspired me and Dance Song for the Nyau Dance (2003) and Nonyana, the Ceremonial Dancer (1994) are rather based on Tracey’s texts than on traditional music itself. It was possible for me to derive some tendencies in African music by listening to these recordings, e.g. the descending melodic lines, as well as question and answer motifs.

BS: Could you tell me more about your recent compositions and current projects?

SG: I am currently experiencing a surge of creative energy. I have recently completed a new symphonic poem for the Cape Philharmonic Orchestra (commissioned by SAMRO). It is called Figures in the Mist/Gestaltes in die Newel and is based on Khoisan culture. It consists of six movements, each of them illustrating an aspect of San lifestyle. The first movement depicts the birth of light (this is based on an old Khoisan legend). The remaining five movements portray elements such as the warm sun on the dessert, the stars in the night, rock paintings and finally also a wild hunting scene. The orchestration is very delicate and I often use the xylophone in combination with other instruments. My aim is to create a sense of transparency, but also to exploit the soloistic qualities of the various instrument groups. This can also refer to the simultaneous use of staccato and legato articulation that appear in my recent piano works.

I have just finished the new piano suite My Jaargetye, as well as the piano quintet A Venda Legend. These works were written for you [Ben Schoeman] and the Odeion String Quartet. I am also very anxious to start working on my Concerto for Viola and Orchestra, which will be dedicated to Jeanne-Louise Moolman. Many of the colours and melodic ideas in these works have appeared to me in my dreams.

BS: BS: You started composing in an “African” style at a relatively late stage – this reminds me of Matisse, who changed his style later in his creative career in e.g. his Gouaches Découpes, or of Hans-Georg Gadamer, who started a new creative phase close to his retirement - after his book Wahrheit und Methode had been published. You have already mentioned that you are experiencing a creative surge – was your Damascus moment responsible for this, or was there something else that sparked this creative energy?

SG: In 2003 I was appointed as the Composer-in-Residence at the University of Pretoria. This was a definite highlight for me and inspired me to write many new compositions.

BS: Do you find it upsetting when a new work only receives one performance? Is this typical of the times that we are living in?

SG: I would rather say that this is a typically South African phenomenon. There seems to be a cultural indifference here and it already started in 2000 when all the provincial arts councils and symphony orchestras were closed. Amidst this apparent indifference, there are some positive moments. I received a telephone call this morning from the Northwest University who decided to award me their very first Chancellor’s Medal for my contributions in the area of music. I am also very pleased that many of my works are performed in other parts of the world. My String Quartet (Song of the African Spirits) will soon be heard in Australia and in the USA.

BS: It is also wonderful that DOMUS (Documentation Centre for Music) and the Odeion School of Music are hosting a Symposium on your works at the University of the Free State.

SG: This Symposium will take place in Bloemfontein between 10 and 12 August. It will include concert performances of my works (including two world premiere performances), and several academic papers will be presented as well. I am greatly looking forward to this event.

BS: You are one of South Africa’s most important music critics and have written many compact disc reviews for UNISA’s journal Musicus. Do you have favourite pianists of the present day or the past, and did any of these artists have an influence on your music?

SG: I do enjoy the clarity in Murray Perahia’s playing and then I also appreciate the many colours in Walter Gieseking’s Debussy-playing. These two pianists exemplify important elements in my piano works, namely clarity in the percussive and articulated passages, as well as poetry and colour in the more introspective movements. I also appreciate the very transparent and cantabile playing of Sergey Rachmaninov.

BS: In conclusion, what do you regard as the greatest success of your career?

SG: Musicologists have described my style as immediately recognisable and said that I have a distinct compositional voice. The reason for these statements may be the way in which I combine African impulses with Western structural principles. I am also certain that the rhythmic vitality in my music is appealing to young performers and it makes me very happy that many of my works are often performed by young musicians.

Interview by Ben Schoeman

Oringinally published 23.07.2012

|

Related Entries |

<< Back to Focus On << Back to All Features |